Why the guitar?

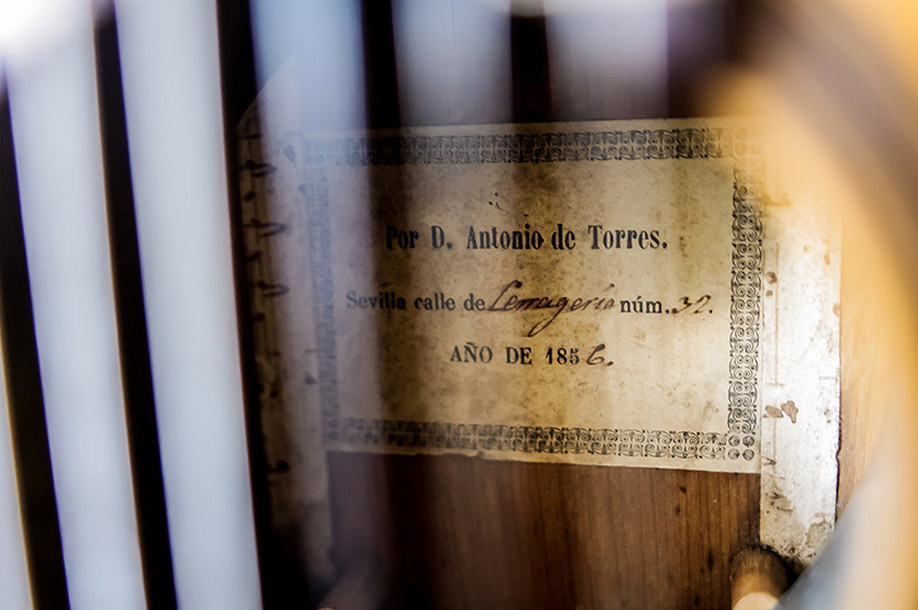

The egg slicer didn't sound all that bad at all… I was just ten years old at the time. Whenever there were boiled eggs for breakfast, the following scene unfolded. Before the egg found its way onto the metal strings of the “slicing boy”, I had become completely absorbed in the irrational twanging of this quintessential invention of the 1970s. The egg meanwhile got cold and at Christmas, I was given my first guitar called “Klira [jangler]”, which describes exactly how it sounded. But, with no means of comparison, I was happy. At the time, of course, I had no idea that two decades later I would play the world’s most famous guitar, the legendary 1856 “Leona” by Antonio de Torres.

I was born into a musical family in Linz on the Danube. My mother was a singer and my father a solo cellist at the Stuttgart State Opera. I, of course, wanted to do my own thing, and that led to the guitar. I first heard the classical guitar on an LP by John Williams, who was later to give me lessons in Córdoba. However, he was quickly rivalled by Jimi Hendrix. The experience soon resulted in my first electric guitar, a very nice Gibson SG Standard in cherry red, followed, of course, by my first bands. They spanned fusion to the free jazz quartet EXTEMPCORE. By that time, though, I was already studying music.

I played my first concert in the wonderful acoustics of the famous abbey on the Scottish island of Iona - Bach, Villa Lobos and improvisations. Even before my “Abitur” exam, as a young student I had already had lessons from my future university professor. At the time, though, I was still torn between music and astronomy. In the end, I chose music, because its emotional dimension seemed to me to be more important in human terms.

Feeling the magic for the first time

In the mid-1980s, my friend, art historian and guitar collector, Dr Michael Herrmann visited me in Cologne and showed me his 1888 Torres guitar. I ended up playing my entire repertoire on this amazing guitar at the kitchen table deep into the night.

It was like being on a trip and and I realised with crystal-clear clarity that this was to be my calling. With the Torres, a transformation from instrument to music, wood to sound, takes place in a hitherto unprecedented way - it leads to a transcendental experience.

This feeling was particularly fundamental when playing Bach. A spiritual force is released in the Torres sound concept that immediately fuses with his music. In this state of intense harmony, my body unites with the sound, I am one with the instrument as the boundaries between subject and object blur. It is as if my entire body, and not just my finger, is plucking the instrument, bringing it to life. In 1991, I recorded the “Guitarra Española” and “Albéniz” albums on this guitar for EMI Classics, the world’s first Torres recordings ever.

Artistic feeling of power

In 1978, I played with my free jazz quartet EXTEMPCORE to a large audience in Cologne at the first Jazz House Festival. Suddenly, I was playing alone with my e-guitar, improvising with everything I had during a 12-minute solo, with neither score nor plan. “I was completely at one with myself, I felt how every single sound etched itself into audience’s consciousness. Of course, I didn't have to fulfil any expectations, as in classical music, where it is case of following the notes. There was no right or wrong, only all or nothing.” This gave me not only a tremendous sense of freedom and exhilaration, but also an enormous feeling of power stemming from the interaction with my audience.

I felt how everyone was listening spellbound. And I carried this feeling of playing, the primal musical forces, into classical music. From free jazz on the Gibson to Bach on the Torres. It may sound impossible, but it is true. It was a key experience: direct feedback and no stress. Although I don’t play the electric guitar any more, the feeling of being “in flow” that I experienced back then is still there.

The crash

It happened at the end of my studies. In the middle of a Bach partita, my mind went blank. The beautiful hall in Brühl was sold out, the press was there, including my publisher. Therefore I was under a lot of pressure, and suddenly, in the middle of the seemingly endless fugue, my mind simply went blank and I couldn’t go on.

I had to leave the stage. I was devastated, completely numb. It was a miracle that my heart was still beating. However, I pulled myself together, returned to the stage and my buzzing audience, left the Bach as it was, and continued with the Giuliani.

How could this happen, and why? It had nothing to do with my preparation; I had played this long work many times and won some competitions with it. No, it was fear. Fear of failure, of not meeting expectations: “I can't afford to slip up now!” These ideas become paramount; you can no longer control them. And then it happens. The psyche cannot withstand the stress any longer.

After that, it was several years before I played Bach again. I felt as if I had misused him for my ego, in an act of self-to promotion. And this was the revenge.

From fear to music

Today, I use a method that I pass onto my clients. We free ourselves from the fear of failing in front of an audience by tapping into the emotional power and expression of the music and by approaching playing and practising in a relaxed, yet focused and stress-free manner. To start with, we can simply play for ourselves. And we have nothing to fear from that, do we? We know then that we have given our best for the sake of the music during rehearsals and can now step onto the stage confidently, without fear and with pleasure.

Add to this two of my core principles or leitmotifs, if you like. Only play pieces that really inspire and challenge you, as only then will you have the energy to invest in practising. Only play pieces that while difficult for you, do not overwhelm you, because you want to be able to play them perfectly in a reasonable amount of time. In the end, what cured my fear was my love of music.

Why am telling you all this?

It is a mirror of my artistic journey. Ultimately, I am always driven by the artistic message that cannot be expressed in words.

It is how I approach my work as a composer and arranger. When I play the d-minor partita with the Chaconne, I aim to get at least as close to Bach's spirit as the violinist to his original. We are dealing here with the inherent idea, with the absolute, and how it can be expressed naturally on the guitar. It does not work with every piece, of course, but with very, very many.

When I compose a new symphonic work, I benefit a lot from engaging with sound colours. Conversely, composing helps me when tackling how to interpret other works. I can give pianists new takes on Chopin, for instance, and inspire them to develop a deeper understanding of his music.

In an on-going process of self-optimisation and many years spent supporting numerous clients, I am now experienced in guiding those who really want to learn, and to put into practice what they have learnt, along the right path. It is the path to the true goal of playing wonderful music on the guitar better and with a greater sense of fulfilment